Sysmex -$SSMXY/6869JP

10.30.25

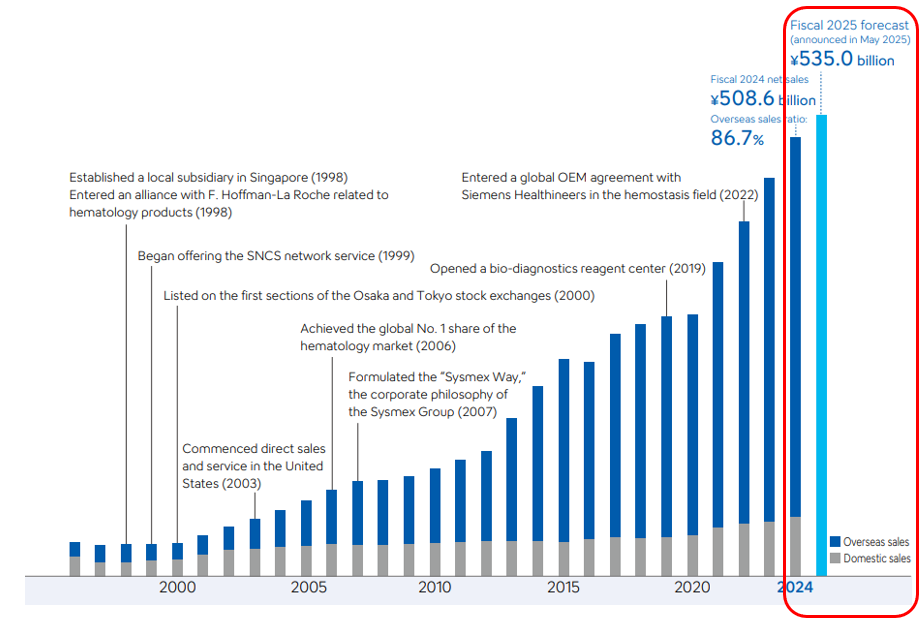

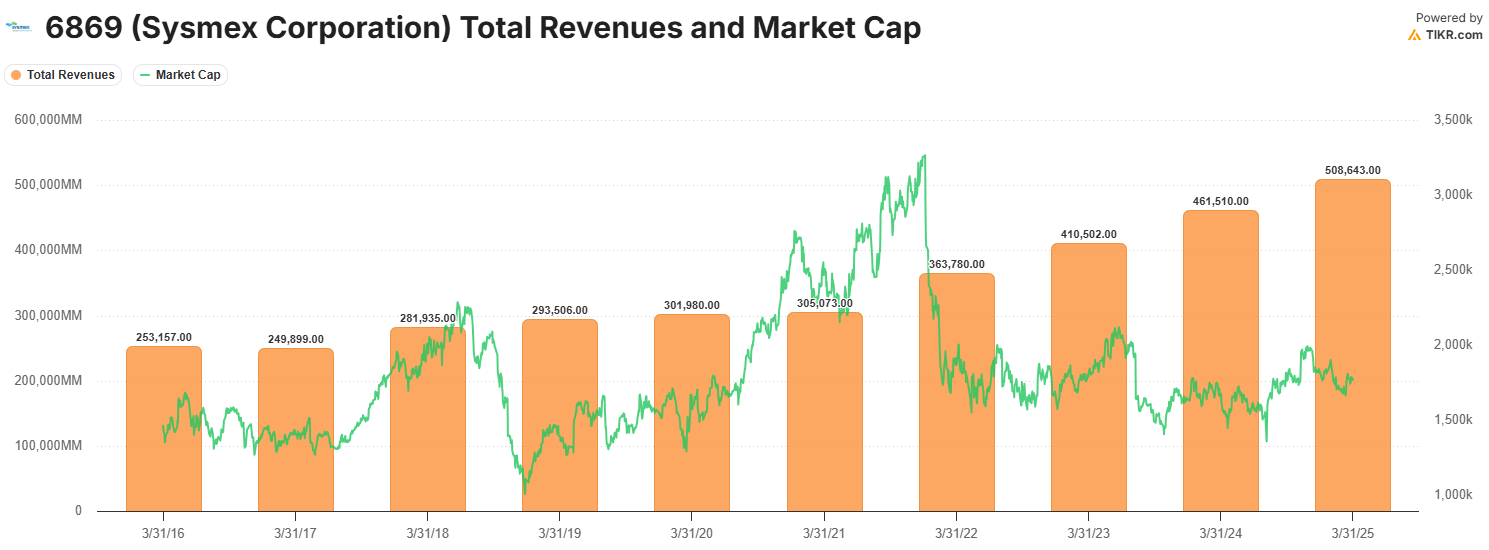

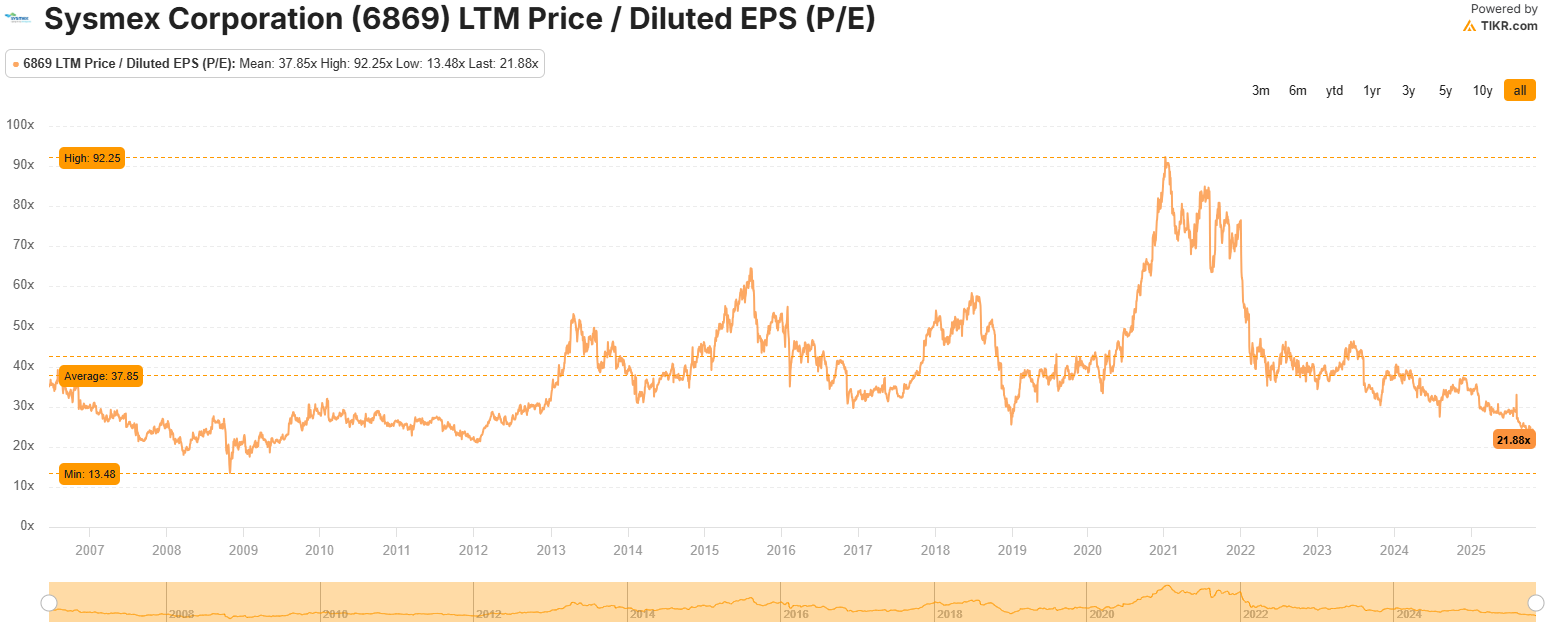

I’ve been following Sysmex—the world’s leading player in blood testing instruments—for a few years now, first when it traded at ~70x during Covid. However, in the past year, the stock has fallen roughly ~40%, which I was quite shocked by, hence for my write up.

There is a few things going on that has pushed this stock to be de-rated, and almost crashed ~50% this year.

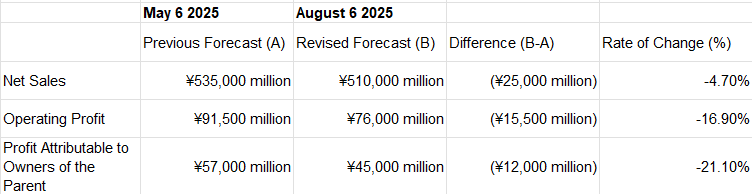

1) Guidance was pulled twice this year: once in May and now in Aug.

2) China: structurally tougher, not just cyclical H1 FY26 China sales down sharply YoY; due to policy pressure, tenders, localization, and value-for-money scrutiny. This is not just for Sysmex, as I did my read-across, similar players in the IVD space has stated the pull back from the China.

3) Sysmex is currently upgrading/updating their ERP order systems, hence some of the new orders for this year has not been able to get into the systems.

4) Combining these things, they are also maintained their cost base, leading to a bit of operating -deleveraging. They are also investing in new growth areas are not yet carrying their weight Life Science, medical robotics, regenerative medicine, which are still small and investment-heavy. These are positioned as future profit drivers, but near term they are R&D- and SG&A-heavy, margin-dilutive, and operationally complex.

Despite these headwinds, which I believe are more transitional/slight errors in management (not communicating this earlier), I still believe the core of this business holds strong advantages and does not deserve the ~50% drawdown. And perhaps now presents a buying opportunity at an attractive valuations.

The last time it traded at ~21x, it was back in 2012.

Overview:

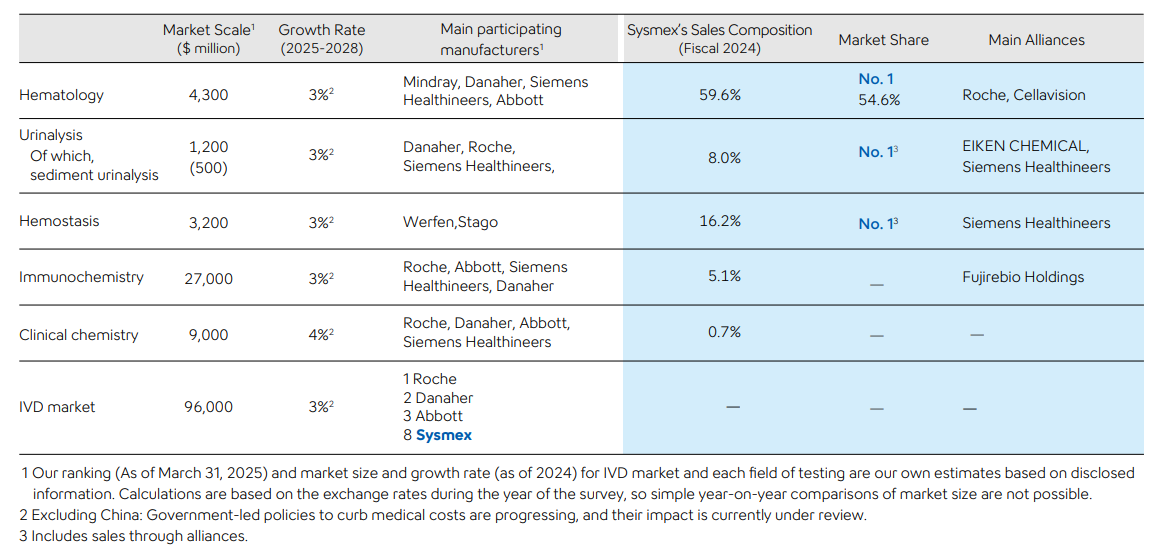

Founded in 1968 in Kobe, Japan by Taro Nakatani—whose family still remain shareholders (>5%) of the company—Sysmex has grown into the global leader in in-vitro diagnostics (IVD) for blood testing. They hold the #1 position across mulitple and important niches - mainly in hematology (blood testing - everytime you get your blood taken for samples, on the backend, they are probably using a Sysmex analyzer machine to provide the results, as they hold more than 50% global market share), homeostasis (~35% share) and urine analysis testing.

The business is attractive, as it sells testing instruments at low margins but generates the majority of its profits from recurring, high-margin reagent and service contracts—the “razor-and-blade” dynamic that locks in customers and ensures steady growth. Over 70% of Sysmex’s revenue and an even greater share of profit come from this recurring base, supported by an installed instrument fleet that is replaced every 5–7 years.

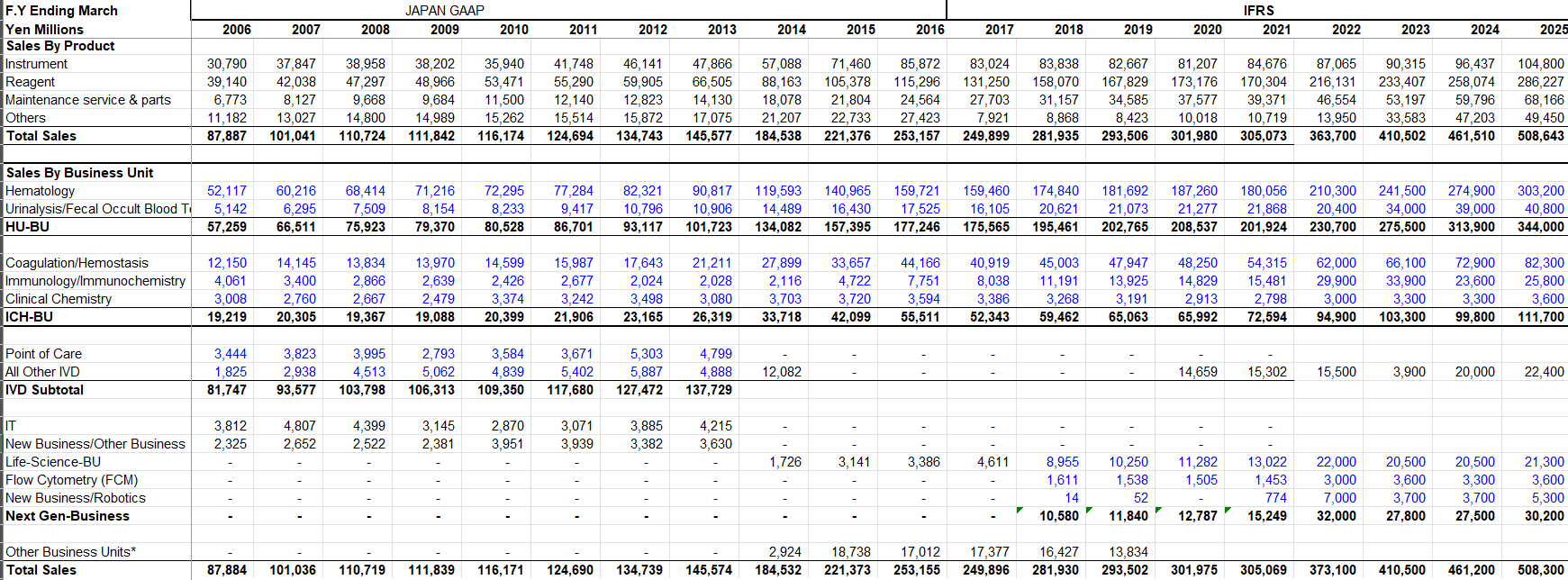

Geographically, the business is well diversified—28% of sales from EMEA, 26% from the Americas, 24% from China, 13% from Japan, and 9% from Asia-Pacific. The core haematology segment (~60% of sales) measures and analyzes blood cells for diseases like anemia and leukemia, while haemostasis (16%) tests clotting function for disorders such as hemophilia and DVT. Sysmex also leads globally in urinalysis (~9% of sales) and has smaller but fast-developing positions in immunochemistry and life sciences (this is where the next phase of growth is aimed at for the company), focusing on Alzheimer’s diagnostics and molecular testing. It maintains long-standing partnerships with Roche (distribution in haematology) and Siemens (reagent manufacturing in haemostasis), though management has signaled interest in taking greater control of reagent production over time. Despite temporary headwinds—particularly in China, where domestic champion Mindray has benefited from “Buy China” policies—I believe that Sysmex still retains formidable competitive advantages through their technology, reliability, and regulatory trust.

Management has responded to these challenges by expanding local production in China and deepening its footprint in fast-growing markets such as India and Brazil, while opening higher-margin opportunities in haemostasis reagents.

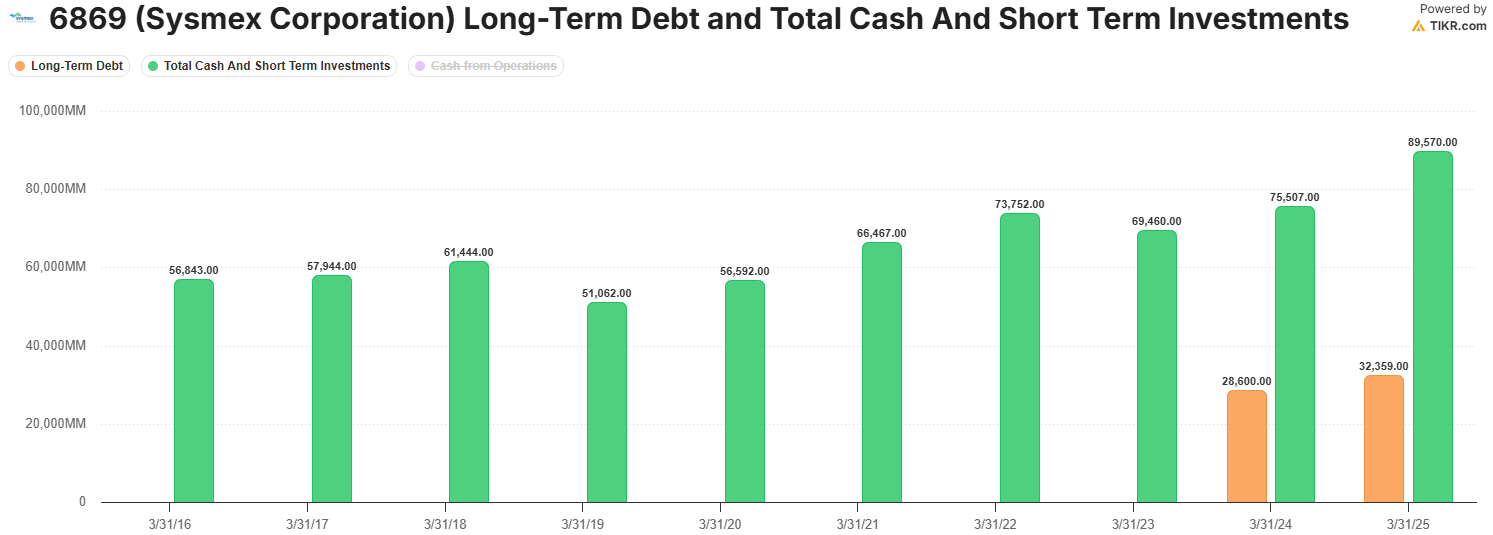

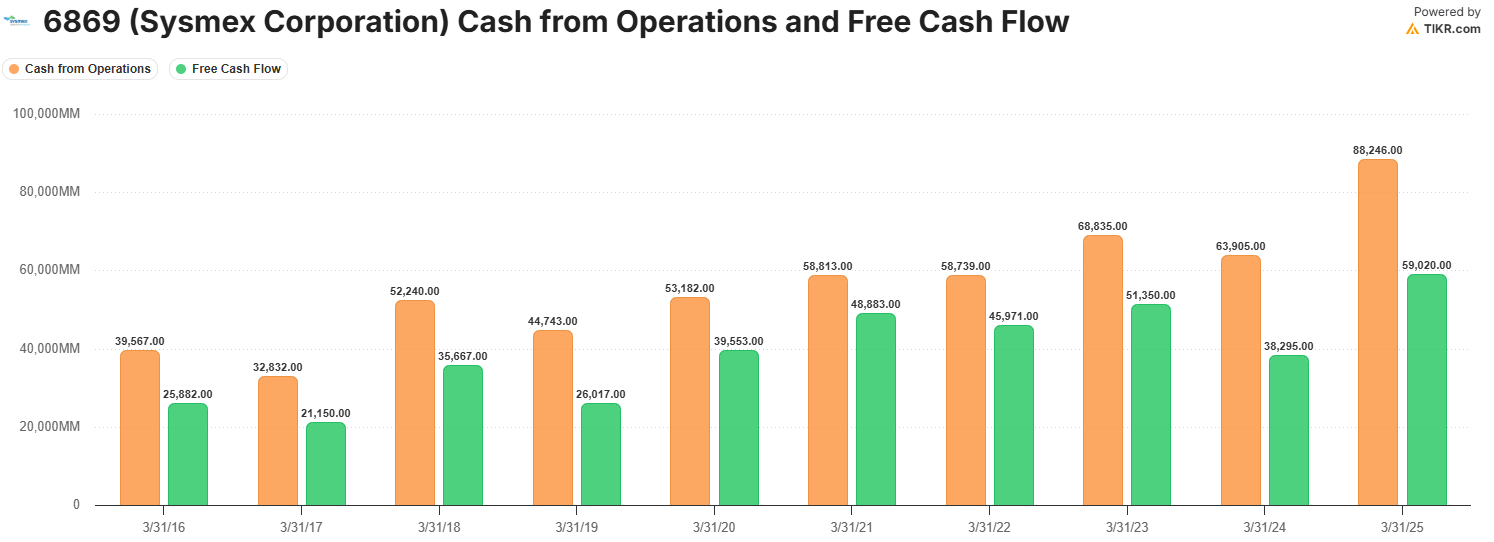

Lastly, Sysmex has a very strong balance sheet, characterised by a net-cash balance position, steady 17% operating margins, 13% ROIC, and a decade-long record of 12% annualized dividend growth.

Combining the above points, all at a time when the stock has been weighed down by China-related headwinds and a few operational challenges—which I view as largely transitional and short-term—Sysmex now trades at a historically low valuation that offers an appealing entry point for long-term investors.

Breaking down the basics:

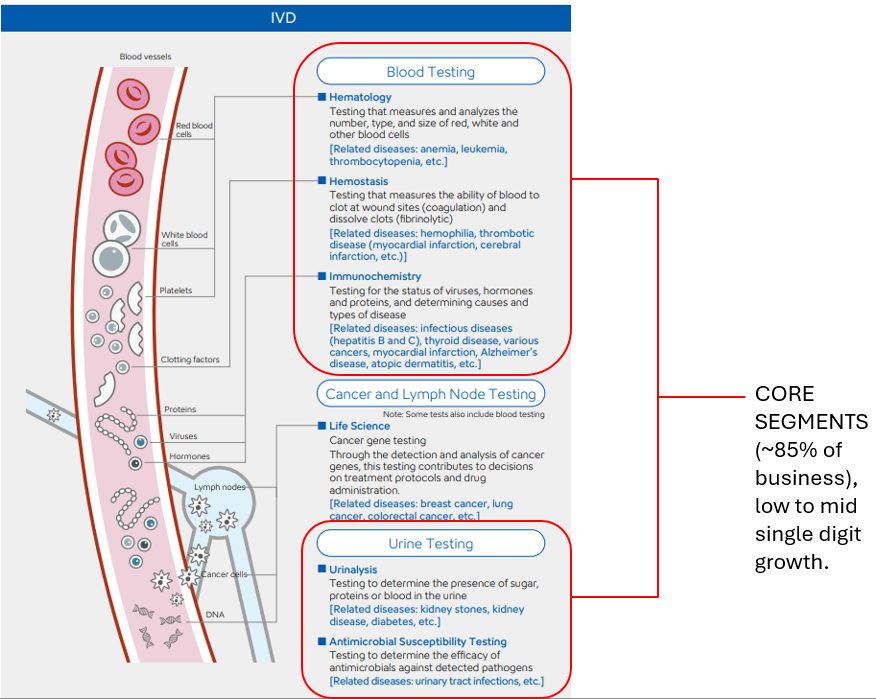

Sysmex is a diagnostic medical equipment manufacturer operating within the in-vitro diagnostics (IVD) segment of diagnostic medicine. Broadly speaking, diagnostic medicine can be divided into in-vivo (in the body)—such as imaging technologies like X-rays, MRIs, and EKGs—and in-vitro (in the lab) diagnostics, which analyze biological samples outside the body. Within in-vitro diagnostics, tests are generally categorized as either routine or specialized.

Sysmex focuses primarily on routine testing, including hematology (blood), urinalysis (urine), and coagulation (blood clotting), while maintaining smaller operations in immunology and clinical chemistry, which are more complex and specialized in nature. Hence, the more routine = less specialized and more commoditized, however, what routine tests lack in specialization, they make up for in volume - as you can imagine, there needs to be mulitple different types of blood tests needed at the point of care for any health check-up.

Razor-razor blade model:

At the core of the IVD business are two essential components: instruments and reagents. Instruments are the machines that perform the analysis, while reagents are the specialized chemicals used to detect and measure biological markers. Sysmex sells its instruments either directly or through distributors to hospitals, diagnostic laboratories, and outpatient testing centers. Procurement decisions are typically made by hospital administrators based on annual budgets and government reimbursements. Reagents, on the other hand, are sold separately and generate recurring, volume-driven revenue tied to patient testing levels.

Because IVD instruments are often designed for specific applications—such as hematology versus urinalysis—laboratories usually operate multiple systems for different test categories. Routine tests are generally reimbursed under public healthcare systems in major markets like Japan, Europe, and the United States, which ensures stable demand. Sysmex and peers typically sell or lease instruments at low margins to secure long-term reagent contracts, which are high-margin and recurring. Manufacturers also offer ongoing maintenance and service contracts as part of the package. The business model mirrors that of printers and ink: the instruments (“printers”) are sold at or near cost, while the reagents (“ink”) generate the bulk of the profits through continuous use over the equipment’s lifespan.

Long Product Cycles and Strong Recurring Revenue Capture:

Sysmex's instruments are generally closed systems, meaning reagents are specifically engineered for each equipment platform—an industry-wide standard that ensures high reagent capture rates. While Japan historically had standalone reagent suppliers that could displace domestic instrument makers in select categories, this approach has largely faded because instrument makers have increased compatability for their systems & solutions (it puts the customer at risk for libability/insurance should they decide to use third party reagents).

The replacement cycle for diagnostic instruments varies depending on usage intensity, maintenance, and clinical setting. Under typical medical lab conditions, systems operate for 7–10 years, though replacements can occur as early as 3–5 years when technology advances meaningfully. Hospitals and labs consider multiple factors when evaluating new systems, including test menu breadth, throughput speed, automation capabilities, reagent logistics, sample requirements, accuracy and precision, ease of calibration and maintenance, data integration, and physical footprint. Upgrades that materially enhance workflow, accuracy, or efficiency can accelerate replacement timing.

Once installed, each analyzer becomes a multi-year profit engine, driving recurring, high-margin reagent consumption and service contracts tied to patient testing volumes. This equipment-anchored reagent model ensures stable and predictable revenue streams that scale with utilization rather than depending solely on capital cycles.

History of IVD and Japan's rise:

Before World War II, physicians conducted diagnostic testing manually—relying on physical examination and basic lab work rather than automated instruments. In hematology, for example, blood cell counts were performed under a microscope, a time-consuming and error-prone process. This changed in 1953, when Wallace Coulter, a U.S. scientist, invented the world’s first automated blood counter, the Coulter Model A—a breakthrough that paved the way for the modern IVD industry. (Coulter’s company would later become Beckman Coulter, now a subsidiary of Danaher.)

Following the war, during the 1960s–1980s, Japan began building its own domestic medical equipment industry to compete with U.S. manufacturers. Japanese firms entered nearly every segment of the IVD space—clinical chemistry, immunology, hematology, and imaging—leveraging their precision engineering capabilities and manufacturing excellence. By the 1980s, Japan had become a global leader in medical diagnostic technology, known for its high-quality, reliable systems and innovations in “system analyzers,” which offered higher throughput and automation compared to earlier models. This became their stepping stone to really dominate the routine hematology space.

In the early 2000s, rising healthcare costs prompted the Japanese government to reduce reimbursement rates, an unintended but ultimately positive development for the industry. Facing a smaller domestic market, Japan’s diagnostic equipment manufacturers were forced to expand globally.

Two business models emerged:

- Full-stack manufacturers producing and selling their own branded products (e.g., Sysmex);

- Contract manufacturers (OEMs) supplying components or systems for global player (e.g., Hitachi Hi-Technologies, which manufactures analyzers for Roche Diagnostics).

Today, the global IVD market is dominated by four major OEMs—Roche, Abbott, Danaher, and Siemens—which together control roughly 40% of global market share. All four are headquartered in the U.S. or Europe, yet their dominance is underpinned by a supply chain deeply intertwined with Japan. Many of these companies rely on Japanese contract manufacturers to produce key diagnostic instruments, particularly blood analyzers, an area where Japanese engineering and precision manufacturing have set the global standard. For example, firms such as Hitachi Hi-Technologies supply analyzers for Roche Diagnostics, and similar partnerships exist across the industry. As a result, even though the market leadership appears Western on the surface, the technological and manufacturing backbone of the IVD industry remains heavily reliant on Japan—a dynamic that underscores the strategic importance of Japanese firms like Sysmex, which uniquely design, manufacture, and commercialize their own systems end-to-end.

Hence, it is really difficult for new entrance to enter the market - not only will they have challenges on procurment via the supply chain, but they also need really high R&D budgets, estabolish strong sales networks, and decades of learned technical know-hows. For example: think of the make up of an MRI machine, which requires sourcing and calibrating thousands of components from specialized suppliers around the world. Even a well-funded startup would face a steep, multi-year climb to reach commercial readiness.

The case of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos—whose story was chronicled in The Dropout (Hulu/Disney, 2022)—illustrates just how unforgiving this industry can be when technological and regulatory standards are ignored.

Furthermore, the IVD equipment industry is heavily regulated, with approval requirements determined primarily at the federal level, often resulting in product variations across regions. Because test accuracy directly impacts clinical decision-making and patient outcomes, most countries enforce strict quality control protocols. In Japan, for example, manufacturers must pass both internal and external verification tests. Internal tests are conducted by the company itself to validate performance claims, while external tests involve government agencies sending standardized samples to confirm that the instrument’s results meet regulatory benchmarks.

These standards have over the last 20 years, progressively been tightened, creating strong hurdles for any player to enter. As players like Sysmex refine their technologies and compliance processes, they effectively set the benchmarks that regulators use—further entrenching their competitive position. Companies like Sysmex, which consistently meet or exceed these evolving standards, not only secure ongoing market access but also help shape the definitions of quality and accuracy across the industry.

The IVD Market & Sysmex's competitive positioning:

- Sysmex operates in IVD markets where a small number of players dominate globally. While giants like Roche compete broadly across core and highly specialized diagnostics, Sysmex focuses on niche yet routine segments—Hematology, Urinalysis, and Hemostasis—where testing volumes are high and switching costs are significant. In these areas, Sysmex holds dominant market positions, with roughly 40–50% share in each segment. These three specialties account for nearly 85% of Sysmex’s annual revenue and together represent about 9% of the overall IVD market (Hematology: 4.3bn, Urinalysis: 1.2B, Hemostasis: 3.2B out of a ¥96B IVD market), implying Sysmex controls around ~4-5% of the global IVD space through targeted leadership in its chosen domains.

- As mentioned, Sysmex has been shaping hematology diagnostics for decades. Launching Japan’s first hematology analyzer (“blood counter”) in 1968 and built a model around selling analyzers, reagents, and training doctors and hospitals. As the industry shifted from manual to fully automated systems, especially from the late 1990s into the 2000s, Sysmex kept upgrading its technology and pulled ahead—particularly in Japan, then globally.

- For example: their current XN-Series analyzers are a good example: they can run up to ~900 tests an hour versus around 300 for the #2 player (Danaher), while maintaining extremely high precision. That precision edge is rooted in their engineering culture: Japanese manufacturing (and Sysmex in particular) emphasizes incremental improvement and ultra-reliable, high-spec hardware. These instruments are complex, tightly built systems—tens of thousands of tiny components working together—which is why many of the analyzers themselves are still produced in Japan, even if reagents are made elsewhere.

- Furthermore, a less obvious strength for Sysmex is how early they embraced “connected” instruments. Long before IoT became a buzzword, they were building remote monitoring and control capabilities into their analyzers in the 1990s. Through their Network Communications Software, Sysmex tracks instrument status and reagent levels in real time, helping labs avoid downtime and flagging exactly when supplies or maintenance are needed. This always-on support model makes life easier for customers and is a big reason Nomura estimates Sysmex’s retention rate at roughly 99% over the past two decades. It is also how they are able to increase their value proposition for the customer as well, and sell more into the sales channels.

- Another key edge for Sysmex is its local reagent supply chain. Large hematology analyzers can require huge reagent volumes (e.g., ~20L or ~5,000 tests), which are expensive and inefficient to ship long distances. To solve this, Sysmex has built reagent production bases across major regions—Japan, China, the U.S., Brazil, Europe, and more—so they can supply customers locally. This setup is hard and slow for new entrants to replicate, reinforces Sysmex’s installed base, and matters financially, since reagents (not the analyzers) are where most of the profit is made.

- The obvious risk—the elephant in the room—is why a giant like Roche or Abbott couldn’t just decide to crush Sysmex in hematology, urinalysis, and hemostasis. On paper, they have the capital, brand, and global reach to do it. In reality, these segments are relatively small slices of the much larger IVD universe (roughly 20% combined), mature in their growth profile, and already dominated by Sysmex. For a big diversified player, the incremental R&D, capex, and multi-year regulatory/validation cycle (often 4–7 years) required to build and roll out a competing platform just doesn’t move the needle enough versus focusing on larger, faster-growing areas like immunochemistry and molecular diagnostics.

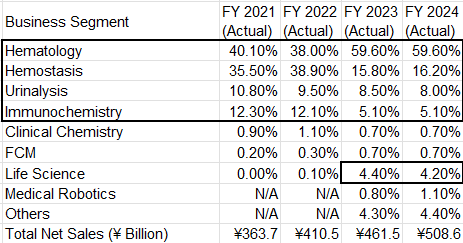

Sysmex's Segments:

Sysmex has 4 core segments, you can see below, and the "others" I would catergorize as newer bets that they started investing in about 7-8 years ago.

Sysmex’s core is hematology. The company has built a dominant global position with more than half of the high-end hematology market, supported by strong shares across Japan, EMEA, Asia-Pacific, and solid penetration in the Americas and China. This footprint did not happen by accident; it came from reliable analyzers, automation, uptime, service, and continuous product refreshes. Hematology is a routine, first-line test in virtually every hospital, which means stable, high-frequency volumes and attractive reagent pull-through.

In 2024/25, they are trying to roll out the new XR series analyzers (see below): new features are more advanced cell analysis and automation (including flow cytometry-like functionality) into standard workflows, tightening Sysmex’s hold on its installed base rather than simply being a cosmetic upgrade. I would argue that part of the challenge has been getting customers their new machines, which has strongly weighed on sales and the derating of the stock. These are massive machines, that takes time to ship and install and get up and running. With the macrouncertainty (i.e., Tarrifs) I suspect that the sales conversion is being stalled out longer, hence for the flatish growth.

Hemostasis is the second structural pillar. Coagulation testing is mission-critical for surgery, ICUs, stroke and thrombosis management, with more specialized reagents and higher value per test. Sysmex has a strong global position here as well, historically sharing economics in certain regions through a partnership model but increasingly looking to pull more of the value chain in-house. Done sensibly, that mix shift can lift margins and deepen integration with its hematology base. Despite recent cyclical softness and some reagent volume pressure, the medium-term logic is unchanged: hemostasis behaves like a smaller, specialized version of the hematology engine, with good stickiness and solid economics.

Urinalysis is a steady, supporting franchise. Sysmex is particularly strong in sediment urinalysis—the more complex, higher-value part of the market—where it holds significant share and sells both instruments and reagents. The strategy of bundling chemical and sediment analyzers into integrated systems makes life easier for labs and reinforces Sysmex’s ecosystem.

Immunochemistry is the most credible internal growth lever from here. Sysmex is not trying to be a full-line Roche or Abbott; it is selectively attacking niches and customer tiers (for example in China and Asia) where it can compete on automation, workflow and economics. It leverages the same relationships, service infrastructure and quality perception built in hematology.

Both hematology and hemostasis have been hit by China’s recent push to cut healthcare costs and favor local suppliers, which has weighed on instrument demand and reagent pricing. I don’t view this as a Sysmex-specific failure as much as a macro and policy issue: most multinational medtech players are seeing similar pressure as China leans into localization, volume-based procurement, and a more politicized backdrop this year. That said, this overhang is unlikely to disappear quickly, so it’s safer to assume China is no longer a straightforward growth engine and treat conditions there as structurally tougher than the last decade. The flip side is that Sysmex’s dominance and track record in its core categories should still travel. As hospital infrastructure and diagnostic standards rise in markets like India and Southeast Asia, Sysmex is well-positioned to win share and replicate parts of its playbook, using its existing technology stack, reagent model, and automation capability to offset some of the pressure seen in China over time.

“Other Bets” as a nice option to have:

Around 10–12% of sales comes from businesses that are strategically interesting but still early: Life Science / OSNA oncology tools, Alzheimer’s liquid biopsy and ARIA risk testing, and the Medicaroid/Hinotori surgical robot. Of which has grown from ~5% of the business back in 2019 to now around 10%. The catch is that each of these areas is R&D heavy, reimbursement and regulation heavy, and behavior-change heavy.

In Alzheimer’s and dementia, Sysmex and Eisai (partnered in 2016) have made tangible progress. Japan has approved Sysmex’s amyloid blood assay kits, providing one of the first commercial blood-based tools for Alzheimer’s pathology, and in 2025 Japan also approved Sysmex’s PrismGuide APOE genotyping kit to assess ARIA risk for patients receiving anti-amyloid therapies. These moves are strongly aligned with global trends toward earlier diagnosis and safer use of new Alzheimer’s drugs, and they clearly play to Sysmex’s strengths in high-sensitivity blood testing. If successfully approved in the U.S and E.U, this would be a major upside to Sysmex's business, and could put the segment at ~high teens growth.

Sysmex has also moved into surgical robotics through its Medicaroid/Hinotori venture, aiming at the same space dominated by Intuitive Surgical. Hinotori is already approved and in clinical use in Japan, with initial approvals in markets like Singapore and Malaysia, and Sysmex is pushing for a broader rollout. The value pitch is straightforward: a more compact, user-friendly robot in a post–Da Vinci patent world. Since its commercial start in 2020, the business has grown from about ¥0.7bn in sales and 18 units to roughly ¥5bn and 89 units shipped by 2025, with a target of 100 units by year-end—still only around US$30m+ at the group level, so financially tiny. But the trajectory matters: it shows Sysmex is still willing to invest, experiment, and build in technically demanding areas, which is very consistent with how they’ve compounded in diagnostics over the past two decades, even if this shouldn’t be a core part of the investment case yet.

Overall, I still see Sysmex as a high-quality niche leader with a dominant position in its core markets and a resilient, recurring revenue base. The core diagnostics engine is intact and remains the foundation of the story. On top of that, the company has started to branch out into new areas—life science tools, Alzheimer’s testing, robotics—where it has already shown it can ship real products and execute, even if these contributions are still small. Taken together, the strength and durability of the core, plus credible early progress in these adjacencies, matter more than the recent sell-off and the slowdown in growth. In my view, the structural quality of the business still outweighs the near-term concerns.