Initiation on Sportswear - NKE/LULU/DECK 1/4

Historically, clothes had clear lanes. Sportswear was for working out, suits and dress pants were for formal settings, and fashion pieces were their own thing. You could basically tell what someone was doing just by looking at their outfit. Fast forward ~15–20 years, and sweatpants, hoodies, and yoga pants have become the default uniform for millennials and Gen Z. If you told someone in the 1990s/2000s that people would be wearing joggers and technical hoodies to the office or out to dinner, they’d be stunned—but that’s where we are now (90s-20s performance → 10s-20s athleisure → 20s-25 lifestyle ecosystem). “Sportswear” has stretched to cover a much wider range of use cases, and fashion and sport have essentially blurred into one category.

That shift has reshaped the competitive landscape: legacy players like Nike, Adidas, and Under Armour are fighting to maintain their share, while newer brands like Lululemon, On, Deckers (Hoka), New Balance, Brooks, Asics and Amer Sports (Salomon) are pushing upmarket and taking share from them. Despite Lululemon’s YTD performance, you can still argue they effectively created modern athleisure—where comfort, style, and trend all come together. On the positive side, as the category becomes less narrowly defined, the addressable market for players like LULU expands, because their clothing can be worn across occasions: a comfortable dress shirt to work, on a flight, or out to dinner. The flip side is that this blurriness, where fashion, trendiness, and functional athletic wear all overlap also makes the market more competitive. Legacy brands are leaning harder into lifestyle and athleisure (e.g., Nike pushing more versatile apparel), while newcomers are moving up the chain into categories once dominated by the big incumbents (e.g., Lululemon launching footwear). As a result, you have a larger pie, but more players are trying to eat it.

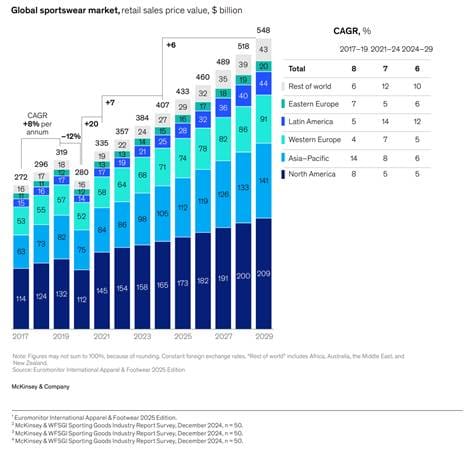

According to market research, the global sportswear market is currently estimated at roughly $200–300 billion and is expected to reach around $400 billion by 2030, implying mid-single-digit annual growth. North America is the largest region, accounting for about 40–45% of global revenue (roughly $95 billion), while Asia Pacific—driven largely by China—is the fastest-growing, with a ~9.2% CAGR[i]. Even though the long-term growth remains solid (~6-7%, 2x-3x of GDP), there has been a gradual softening in recent years, which supports the increased competitive nature of the market. The last 10yrs have played out something like this:

· 2015–2019: Steady 6-7% annual growth, driven by adoption of athleisure expansion.

· 2020–2021: COVID bump, with 10%+ growth as work-from-home made activewear and athleisure everyday uniforms and the rise/increased performance of new competitors.

· 2022–2024: Growth cools to 5–6% as post-pandemic normalization, inflation, and inventory clean-up take some air out of the category. Intensified competition amongst new players and how Nike lost its edge (more on this later).

When it comes to growth drivers, I think about them in two ways. First, you have the classic trend drivers:

· Health & wellness shift – Gen Z and millennials have a preference towards fitness, yoga, meditation, and comfort/casualization. They also tend to smoke and drink less (secular decline) vs previous generations[ii]. One of the reasons that players like a Brown-Forman’s stock has de-rated, and their push towards non-alcoholic beverages is because there are concerns towards changing demographics – towards moderation & health.

· Digital engagement & communities – Direct-to-consumer via Instagram, YouTube, and creator culture builds “communities,” not just customers. Think Strava: ~80% YoY growth to ~40–50 million MAUs[iii]. These groups create strong identities—if your run crew is laced up in ON or Hoka, odds are you’ll end up in the same shoes.

Second, it comes down to how companies innovate on “newness”, which can be an extension of how they position, brand, and design products to match specific customer preferences. It’s not that consumers couldn’t just buy Nike and go for a run; its that newer entrants brought a “refresh” to the category that resonated more with younger consumers. It is what marketing calls “visual tech” – in Hoka’s where you see the maximalist cushioning and in ON you see the cloud pods, which are visually striking designs that shout comfort.

This point is important because it highlights how the industry’s economics have shifted over the last decade. Historically, brands like Nike, Adidas, and Puma relied on wholesale: you’d buy their products through intermediaries like Sport Chek or Foot Locker. That model typically delivered ~40–50% gross margins and ~5–8% operating margins, with growth driven by 3–4% volume and 1–2% price, supported by retailer partnerships and strong brand image.

Today, newer players like Lululemon, Deckers, and ON are built much more around the direct-to-consumer (DTC) experience, where they run their own stores and websites (i.e., more vertically integrated). This typically leads to higher margins, tighter customer data, and more pricing control (fewer markdowns). As a result, they’re often running at ~55–65% gross margins and operating margins in the teens. The DTC’s share of industry sales has grown from ~20% in 2015 to ~35–40% in 2024. That said, it’s not always the right answer—each DTC strategy needs to be evaluated on its own merits. Nike’s aggressive push toward DTC, for example, proved costly and contributed to roughly ~$150bn of market cap being erased!

So, what went wrong with Nike? They really messed up on two things – innovation/product and leadership. While hindsight is 20/20, and I’m obviously looking at this after the fact, their old CEO in John Donahoe (2020-2024) has really been put on the spotlight for his decisions.

If you were in his seat at the time, the move probably felt right. Competitors were taking share, COVID hit, DTC was working well, and Nike already had a functioning DTC engine. The logic was: if Lululemon, Hoka, etc. can do this, why can’t Nike, the 800-pound gorilla, just lean in and do the same thing at scale? So, they went hard into DTC and did it aggressively. The trade-off, though, was less focus on what matters long term: the product and “newness” in innovation.

As they pushed DTC, Nike ramped up spending on customer acquisition (Meta, Google, performance ads) and shifted more business toward single-pair shipments to individual customers, which is structurally more expensive. At Nike’s size—around $50bn of merchandise and ~mid-teens global sportswear share—that’s not trivial. On top of what you are already spending on to maintain the brand, and you now also carry higher acquisition, logistics, returns, and more discounting and promos to keep volume moving. At the same time this was happening, they were also pulling back from wholesalers. While DTC can offer better margins, it depends entirely on the strategy and how strong your product and innovation engine is. Wholesale partners don’t just sell your product—they bring foot traffic, share marketing costs, and create in-store experience and visibility. When Nike reduced its presence, it effectively handed over shelf space to rising brands like On, Hoka, New Balance, and Brooks. Hence, not only has the market become even less concentrated and more competitive than it was 5 years ago, but the rise of the newer brands is also starting to gain even more market-share at the expense of legacy ones.

Conclusion & Outlook: In the 2015–2019 window, investors were willing to pay premium multiples for structurally growing, brand-led stories in Nike, Adidas, and especially Lululemon (industry growth was also in the high-single-digits). During COVID, that premium went even higher as these businesses (both new and old) caught a stronger tailwind (i.e., households received stimulus and “work from home” dress codes seeking comfort became the status quo), which combined, steered these companies into multiples of ~35-40x p/e.

However, as the world normalized post-COVID to the present, the industry had to work through higher inflation, excess inventories, and consumers had already adopted the “newness”. It was no longer rare to see multiple people in a room wearing the same On Clouds or HOKAs—what used to be a trend has saturated. As such, growth slowly moderated and inventory levels grew, leading analysts to de-rate some companies leading into 2025 (along with company specific issues).

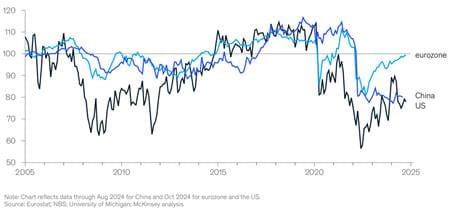

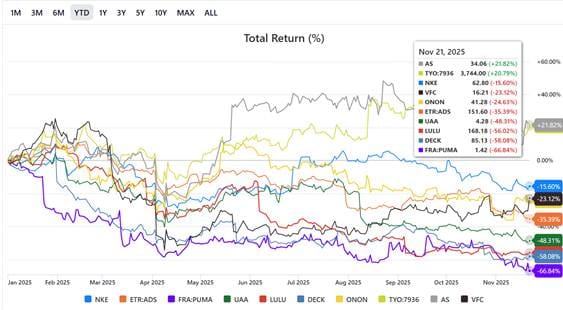

Layered on top of this and through 2025 was a tougher macro and policy backdrop. This year, new tariffs created an additional headache, as companies try to figure out their strategies (i.e., re-routing manufacturing, deciding on to either pass higher costs to consumers or absorb some costs internally, etc.). At the same time, consumer sentiment has rolled over: polling & surveys suggest confidence is weak, credit losses are rising in the US, car loan delinquencies are up, and unemployment has ticked higher (Canada flirting with ~7%, the U.S. closer to ~4%, which is high relative to its recent baseline)[iv][v][vi]. The pressure is most visible in discretionary categories. Discounters like Walmart, Dollar General, and Ross are printing solid numbers and beating earnings, which fits the narrative, as individuals are opting to shop in more discount stores, and thinking twice before making a purchase, especially a pair of sneakers for ~$150. On the capital-market side, a lot of the narrative and investments have also focused on investments in A.I. The combined effect of all this—tariffs, weak sentiment, behavior, and investments into A.I, has put sustained pressure on the sportswear group (a consumer discretionary group). As you will see in the APPENDIX, excluding of Amer Sports (which sits closer to “technical luxury”) and ASICs (Japanese listed), most names have performed terribly this year.

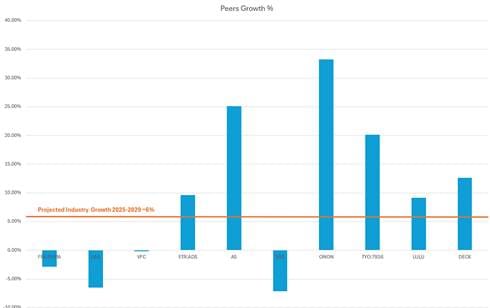

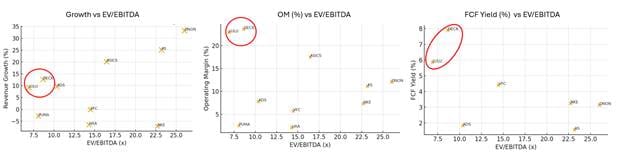

Despite these challenges and the underperformance across the board, it can also create buying opportunities for investors with a longer time horizon and one that validates the businesses for its fundamentals vs macro/policy outlook. As you can see in the appendix, from a valuation standpoint, Decker Brands and LULU looks attractive. Characterized by strong brands, high-single to low double digit revenue growth, strong operating margins (relative to comps), and solid management teams that has delivered high ROIC & continues to push for share buybacks. There is also a potential turnaround angle in Nike (YTD negative ~45%) if you believe they can repair product cycles, reset wholesale relationships, and re-accelerate innovation after a difficult DTC pivot. That said, all three ideas need deeper, name-specific fundamental research.

I will follow up next with a initation coverage piece on each of the businesses that I believe are high quality next.

[i]Athleisure Market Size, Share & Trend Analysis Report, 2030 (LINK). Sportswear Market Size, Share And Trends Report, 2030 (LINK). Global Sports Apparel Market Size And Forecast (LINK). McKinsey & Company: Sporting Goods 2025—The new balancing act: Turning uncertainty into opportunity (LINK).

[ii] https://time.com/7203140/gen-z-drinking-less-alcohol/. A 2023 survey from Gallup found that the share of adults under age 35 who say they ever drink dropped ten percentage points in two decades, to 62% in 2021-2023 from 72% in 2001-2003. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2025/06/07/nonalcoholic-beer-second-largest-category-popularity/83999764007/

[iii] Strava App: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/strava-statistics/

[iv] University of Michigan, Surveys of Consumers. (2025, November 21). Final results for November 2025. University of Michigan. https://www.sca.isr.umich.edu/

[v] Federal Reserve Bank of New York. (2025, November 5). Household debt balances grow steadily; mortgage originations tick up in third quarter (Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit). https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/news/research/2025/20251105 Federal Reserve Bank of New York

[vi] Statistics Canada. (2025, October 10). Labour force survey, September 2025 (The Daily). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/251010/dq251010a-eng.htm Statistics Canada

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025, October). The employment situation—September 2025 (News release). U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf Bureau of Labor Statistics

Appendix:

Fig.1: Sportswear Industry McKinsey

Fig. 2: Market Share Gains (Losses)

Fig. 3: Brand Value Estimates 2006-2025

Fig. 4 Group Performance YTD

- As explained, the whole group has struggled this year.

Fig. 5: Peer Growth

Fig. 6 Valuation Comparisons

- LULU & DECK have traded the below their historic averages.

Fig. 7 Profitability

Fig. 8 EV/EBITDA comparisons

Fig. 9 Consumer Confidence: